About VIII Bogdo Gegen

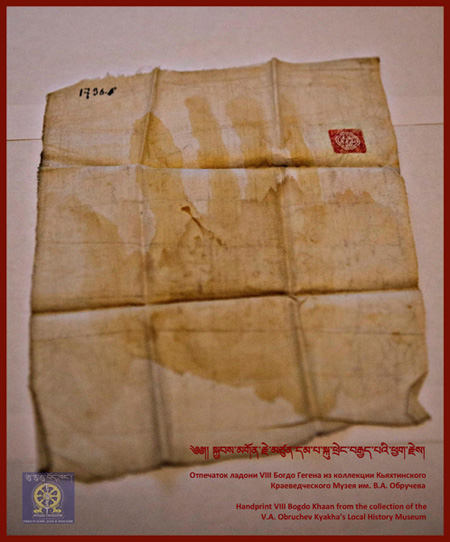

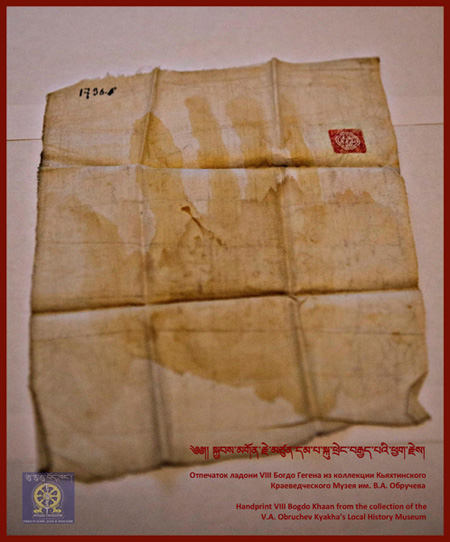

In April this year, the delegation of Tibet House in Moscow together with the son of IX Bogdo Gegen Tugse Ripoche made a visit to the center of Buddhism in Russia - the Ivolginsky datsan. During this trip Tugse Rinpoche met with XII Khambo Lama Itigelov and visited the temples of the Ivolginsky datsan.There a long-awaited meeting with XXIV Khambo Lama Ayusheyev took place in a sincere and inspiring atmosphere. Besides, the delegation visited Yangazhinsky, Egituysky and Tamchinsky datsans, and completed its trip along the Republic of Buryatia in the glorious border town of Kyakhta where the handprint of VIII Bogdo Gegen, the spiritual and secular head of Mongolia, has been kept. We express our special gratitude to Svetlana Apanasenko, the Museum scientific officer, a custodian of Zoological Collection, and Avgustina Abrosimova, the Museum attendant, - the most hospitable person in Kyakhtinsky district.

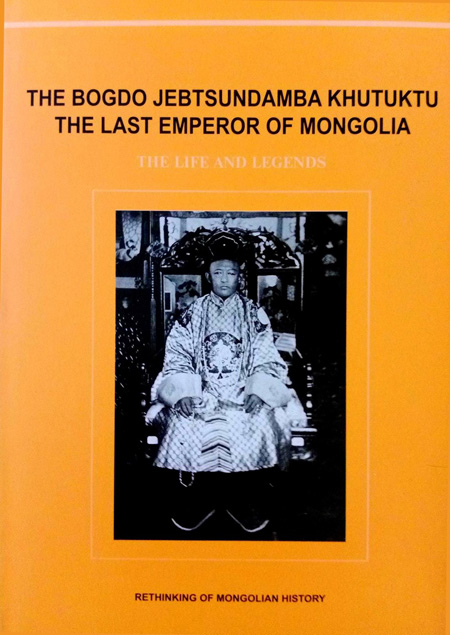

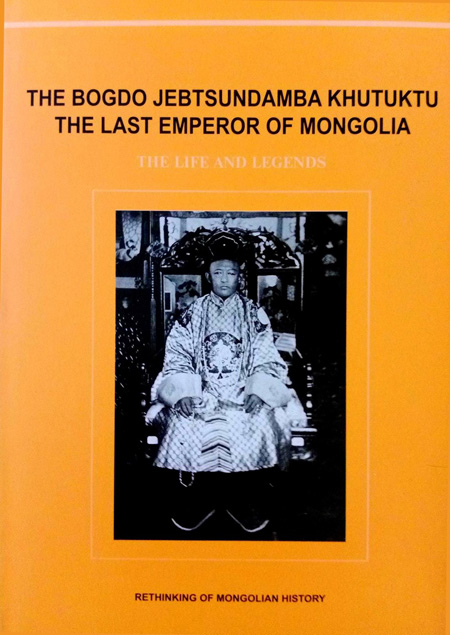

In this regard, we publish the extract from the book about VIII Bogdo Gegen graciously provided us by its author, Ookhnoi Batsaikhan, Doctor of Historical Sciences.

At the residence XXIV Khambo Lama Ayusheev

From left to right): Elizaveta Rybinskaya, a friend of Tibet; Marina Chagdurova, Head of RKF Department;

Olga Tsydenova, the Museum scientific officer, a custodian of Ethnographic Collection; Bair Budaev, the Museum scientific officer, a custodian of Archeological Collection; Tugse Tulku Rinpoche, the son of XIII Bogdo Gegen; Nadya Berkengeym, Vice President of Tibet House; Togi, Director of Mongolia Vip Service; Valentina Badmaeva, the Museum scientific officer, Excursion and Media Department; Ekaterina Kosenko, a representative of Tibet House in Siberia; a guide - Darma Rabdanov, Head of the Russian-Mongolian Friendship Museum (RMF)

VIII Bogdo Khaan from the collection of the V.A. Obruchev Kyakhta’s Local History Museum.

THE MONGOLIAN NATIONAL REVOLUTION OF 1911 AND BOGDO JEBTSUMDAMBA KHUTUKTU, THE LAST KING OF MONGOLIA

By Batsaikhan Ookhnoi (Mongolia)

BRIEF INTRODUCTION

On 1 December 1911, the Mongols seceded from the Manchu empire and declared their independence and elevated Bogdo (Holy) Jebtsundamba Khutuktu to the throne as the khaan of the Mongolian nation.

Since the year 2007, we, the Mongols, have annually celebrated the 29th December as the Day of our National Independence. This process was facilitated by the findings of many Mongolian and foreign scholars on the National Revolution of 1911. A more objective attitude has been taken towards historical studies and a process of reviewing the recent ideologized historical past has begun in earnest. I wish to recount here on how Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was described during the socialist years and the change of attitude towards him, taken place in the post-socialist period.

PRECONDITIONS FOR THE MONGOLIAN NATIONAL REVOLUTION OF 1911

Yakov Shishmarev, a famous Russian diplomat, who spent some 50 years of his life in Mongolia, noted in 1885 when writing about Mongols: “In case conditions are to be created for the Mongols to be united, the khalkhas are certain to lead the movement towards them. Many factors account for that. The most important one is that in Khalkha does reside the reincarnation of Avid Jebtsundamba who all Mongols and khalimags venerate”.

The authority and reputation of the Khutuktu were huge in Mongolia even though he had been found not in Mongolia but in Tibet, that is, not a Mongol but a Tibetan had been identified as the reincarnation and no titles and privileges had been accorded to him by the Manchu Emperor. Because he was so influential that it was noted: “although he is not directly in charge, he can be instrumental not only in Mongolia but also for others beyond her”.

Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu stated in 1909 in one of his decrees: “It is now a time for us to think of the ways to promote Mongolia?s religion and statehood, protect our land and live in peace and happiness for long. If we miss this time, we will have to suffer a great deal and will be unable to control our land, much the less will we be able to live in happiness. If I do not remind you of this, in spite of my knowledge, there is no use for the Mongolian nation to have venerated my eight reincarnations. I, therefore, can not but advise you. . . . You, nobles and officials, think well over the way out and let me immediately know of your views and opinions”.

There is a plenty of information about Mongolian noble?s secret meeting held in Khuree in July 1911. The United states Embassy in Peking informed its Government that the meeting was held in Bogdo?s residence and that it was chaired by him5. The dispatch ought be viewed as showing Bogdo?s involvement in it.

Dobdanov, a buryat who arrived at Khuree on 21 October 1911, noted in his letter to V.Kotvich about the political situation in Mongolia,: “The future of Khalkha?s life is now in the hands of Bogdo khaan only. But Bogdo?s political vision has not been clear so far”.

Dobdanov underlined when writing about the Bogdo: “It is no coincidence for the Khuuktu to have been elevated to the throne as the khaan of the Mongolian nation. He has in fact been so for many years. He had been working for years carefully and unswervingly to show the world that he was the khaan of the Mongolian nation. The coup taken place was an outcome of Khutuktu?s wise policy and the effect of his political wisdom”. His remark ought to be seen as a clear statement of the historical truth that we, Mongols, do not recognize or do not dare to express themselves.

Dobdanov also noted in his letter to Kotvich: „the Mongolian National Revolution was a blow to the Manchu authorities and aided, as such, the Chinese revolution. The Chinese should be grateful to the Mongols for that and should, at least, recognize their situation that is now created”. It shows the importance of the Mongolian National Revolution of 1911 as a subject matter requiring further and deeper studies. It may be possible to view that the Mongolian Revolution of 1911 was a factor in the process that made the Manchu authorities understand that they had no means to oppose to the Chinese Revolution that had spread throughout the Manchu territories, including their remotest areas and had become an overwhelming process.

The culmination of the Mongolian national revolution of 1911 or the enthronement of Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu as the khaan of the Mongolian nation

A very interesting account of the ceremony of the enthronement was provided in „Obugun bicheechiin oguulel” (“Reminiscences of an Old Scribe”) by G.Navaannmjil who had attended it and described what he had seen. He wrote: “The 9th day of the mid winter month came. . . . (We) rode on horseback to the yellow palace in the centre of Ikh Khuree. When (we) dismounted from (our) horses and walked towards its main large gate, there were so many people gathered that it was impossible to see where the crowd ended. Nobles officials, khutukhus and lamas in their official headwear, jackets and variegated deels (gowns) were lined up for the occasion. When Bogdo and Tsagaan Dari (White Tara) came in a solemn pomp, all those gathered kowtowed and became quiet. Bogdo and his consort were sitting in a beautiful Russian four-wheel yellow carriage flying a golden flag. Eight attendants and lamas were carrying the carriage. Before it high ranking lamas and escorts were marching in file. A few nobles in black and wearing swords in red scabbard were leading the group. Many armed guards in their fine uniform were marching in file along the sides of the road. When Bogdo and his consort walked past the central gate of the palace and into the gher-palace, all those high-ranking nobles and lamas followed them. Other nobles were waiting, standing in front of the state palace”.

Bogdo and Ekh Dagina (the Beauty) wore expensive black fox-fur hats with diamond buttons of rank on top, colorful deels and speckled sable-fur jackets. Escorted by nobles, soivon and donir, they were slowly walking on the yellow silk walk prepared for the occasion. Three ceremonial parasols – two with golden dragon designs and one adorned with peackock feather - were held above them from behind. The procession was led by a donir and a nobleman in black with a sword in a red scabbard. Bogdo and Ekh Dagina were supported with their arms by assistants and nobles. Bogdo and Ekh Dagina, after visiting the Ochirdara temple, proceeded to the state gher-palace. Many khutuktus, khans, vans, beel, beis, gung, zasag and taij, entitled to enter the palace, followed them.

Beis Puntsagtseren, a former Mongolian Minister in Khuree, came out with a rather long document and announced loudly that a decree on distributing favors had been issued. All the laymen and lamas, officials and clerks became silent and kowtowed. Beis Puntsagtseren began reading the decree. But it was difficult to hear. With some efforts, I was able to make out: “Bogdo was elevated as Bogdo, the sunshiny and myriad aged khaan of the Mongolian nation and the Tsgaan Dari as the mother of the nation and the reign title would be „elevated by many „. And Ikh Khuree is to be called Niislel (Capital) Khuree. Thus Mongolia was established as a state and a great ceremony was held”.

L.Dendev, a researcher of Manchu viewed Mongolia?s independence of 1911 as “a remarkable exploit that led to Mongolia?s secession from the Manchu, the protection of her national identity and to the establishment of an independent Government in Mongolia” and described those important events in his work.

BOGDO JEBTSUNDAMBA KHUTUKTU AS THE LEADER OF THE MONGOLIAN NATIONAL REVOLUTION OF 1911

The eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba Agvaanluvsanchoijinnyamdanzanvanchigbalsambuu was born in 1869 in Tibet in the family of Gonchigtseren, a well-off financial official of Dalai Lama.

He arrived at Khuree in the morning of 30 September 1874 and received a joyous welcome. The Khuree population was doubled at the news of his pending arrival and there were many nobles among them. Soon afterwards, i.e., in early October 1874, the khans and gungs of the four aimks of Khalkha gathered in Khuree and a formal welcome was arranged for the eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and his elevation to the Bogdo throne. The Manchu Emperor conferred on him the corresponding title and rank along with the golden diploma of entitlement and a golden seal.

Since Bogdo stayed in Khuree all the time following his arrival after being found when he was 5 years old, his life was closely linked to the history of Mongolia. He arrived in Mongolia in a group of seven family members, including his father, mother, elder brothers and Luvsankhaidav, a younger brother.

Bogdo was taught from early on Tibetan and Mongolia writing and religious conventions and Eastern customs and traditions. Old people mentioned that his Mongolian was better than his Tibetan. He was the last khaan of the Mongolian nation, who was enthroned three times and the only gavj (lamaist high clerical degree) out of the eight Bogdos who led the Mongolian lamaist church.

It is often mentioned that when influential Mongolian nobles, close to Bogdo such as Da lama Tserenchimed and Chin van Khanddorj, commander of Tusheet khan league, confided in Bogdo of their views on making Mongolia an independent nation, he decreed to hold a meeting of all the khans, nobles and high ranking lamas of the four Khalkha leagues during the Danshig offering to be performed by the leagues and Ikh shabi in the summer of 1911, and express their views on whether to accept or not the new policy course of the Manchu Government. The meeting has often been referred to as marking the beginning of the movement for Mongolia?s national liberation. The proponents of such approach view the Mongolian khans and nobles as the initiators of the national movement and Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu as their supporter. A deeper analysis of the historical situation would provide a bit different picture.

Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu sent in late XIXth century his emissaries to Russia on a secret political mission. In June 1911. T.Namnansuren, the good nobleman, wrote a letter to Bogdo to alert him against the risks and dangers of the new Manchu policy course being enforced in Khalkha. Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, having reviewed the content of the letter, decreed to convene in July in Khuree a meeting of the khans, vans and

The leading noblemen of the four leagues met in Khuree in the middle of 1911 and convened a meeting of noblemen, where each league and Shabi was represented by four delegates to have the issue of “the need for Mongolia to be an independent state” discussed as Bogdo had decreed a year earlier. But when Sando, the Manchu Amban in Khuree became suspicious the meeting was suspended. But it continued in the summer of 1911 under the pretext of performing a religious service for the benefit of the Bogdo.

The Khans, noblemen, officials and khutuktus and lamas of the four Khalkha leagues and many Shabis met in the summer of 1911 in the office of Khuree?s Erdene Shanzodba under the pretext of performing, by Bogdo?s decree, religious services, and discussed how to oppose to the „new Manchu policy course? and restore Mongolia?s independence. Since it was difficult to reach a consensus decision by many participants who were not free from the persecution of the Manchu amban, a group of people including those noblemen and khutuktus led by the khans of the Khalkha?s four leagues, who were firmly opposed to the Manchu new policy and who believed that it was a time for Mongolia to become independent of Manchu, in the interests of their nation, religion, state and land, held separate consultations in secret, meeting in a gher set up in the woods at the back of the Bogdo mountain.

It was decided by the noblemen?s secret meeting to “send a special deputation to Great Russia, the northern neighbor, to kindly explain Mongolia?s situation and seek an assistance for the foundation of the Qin Government became shaky and it became impossible (for Mongolia) bear foreign officials? and ministers? oppression and exploitation and their complete disregard towards Mongols? interests, although it was necessary to get independent and protect Mongolia?s religion and land, it was very difficult to do so without foreign assistance” and to “appoint Chin van Khanddorj, Da lama Tserenchimed and official Khaisan as the deputation”

The Mongolian delegation took a letter seeking assistance from Russia. It was signed jointly by Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and the four Khalkha khans: Tusheet khan Dashnyam, Zasagt khan Sonomravdan, Setsen khan Navaantseren and Sain noen Namnansuren. Korostovets, a Russian minister in Peking considered “the arrival in Russia?s territory of the Mongol envoys at their own initiative to be useful as a pretext for negotiations (with the Manchu authorities –O.Batsaikhan)”. M. Tornovskii noted, in this connection: “Bogdo the Venerable, could successfully hold, over the heads of their enemies, businesslike negotiations with the Imperial Russian Government to get an assistance for Mongolia. He managed to get the support of the noblemen who believed in the possibility of obtaining their freedom from the Chinese with the Russian assistance.” He wrote that noblemen and lamas met in Khuree in June 1911 under the leadership of Bogdo the Venerable.

The political events taken place after the meeting held in Khuree during the Danshig offering for the benefit of the Bogdo in the summer of 1911 and noblemen?s secret meeting held in the Bogdo mountain show that a provisional government was in effect established in Mongolia. This institution was formalized and was named a General Provisional Administrative Office for the Affairs of Khalkha Khuree on 30 November 1911, after the delegation who had gone to Russia and successfully completed their mission, returned to Khuree.

An important immediate objective of the Provisional Government was to restore and declare Mongolia?s independence. The Provisional Government issued on 1 December 1911, a Declaration proclaiming the end of the years of the Manchu rule and the establishment of Mongols? independence as Sando was being expelled from Khuree. A flag with soyombo, a symbol of national liberation and independence, thus, began to fly in Ikh Khuree.

The Mongolian National Revolution, thus, broke out in the year of boar and resulted in the elevation of Jebtsundamba Khutuktu to the throne as the khaan of the Mongolian nation on the 9th day of the mid winter mongth or 29 Decemer 1911. Obviously, Bogdo?s enthronement was aided by a number of factors. He, for one, was not only the religious leader of the Mongols. He could become, by then, the most popular statesman.

The Mongols considered that Bogdo?s reincarnations were inevitably related to the Chinggis? golden lineage since the Lofty Enlightened Zanabazar, the first Bogdo Jebtsundamba, was the son of Tusheet khan who was of the golden lineage. After his elevation as the khaan of the Mongolian nation, Bogdo Jebtsundamba and Queen Ekh Dagina visited, on the first day of every Lunar new Year, the gher-palace of Avtai sain Khaan, the father of Tusheet khan Gombodorj and set a fire in its hearth. This practice may have been meant to express the continuation of the stately tradition of Mongolia and was supported and followed by intelligent and sensitive Bogdo khaan under the impact of Chinggis descendents and other influential statesmen of Mongolia.

Bogdo’s treatment in Mongolia’s historical studies

After the demise of the Bogdo khaan on 20 May 1924, the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Mongolian People?s Revolutionary Party (MPRP) decreed on 3 June 1924 that Mongolia become a Republic.

It is said in a volume “History of the Mongolian People?s Republic?: Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, leader of the Mongolian Yellow faith was elevated as the khaan of the Mongols and became the wielder of power both in the church and the state. The demise of Bogdo the Enlightened provided a convenient pretext for establishing Mongolia as a Republic”. It did not provide any conclusion. It did, however, contain numerous references to the Bogdo?s Government or references to the effect that the secular nobles and high ranking lamas headed by Bogdo were greedy exploiters.

The following was noted about Bogdo in the “Short Outline of the History of the Mongolian People?s National Revolution” written by Kh. Choibalsan, D.Losol and G.Demid: “The fact that Bogdo caused grief and affliction to the people instead of ensuring their well-being, clearly showed the false and harmful nature of the incarnates like him”.

The “Brief History of the MPRP” had the following to say about the Bogdo: “The Mongolian people?s national liberation movement resulted in the formation of a feudal Government headed by absolute monarch Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and in the proclamation of Mongolia as an independent state21. The third edition of the “Brief History of the MPRP”, published in 1985, concluded: “The Treaty of Oath” adopted on 1 November 1921, gave a powerful blow to the schemes of feudals headed by Bogdo and opposed to the revolution and was of a critical importance in the strengthening of the new people’s statehood and Government”.

The following was noted about Bogdo in “The Experience of the Struggle Successfully Waged by the Party against the Right Opportunists”, published in 1932 by U. Badrakh, one of the main representatives of the Radical Left: “The eighth reincarnation of Bogdo Jebtsundamba contributed, as he wielded power in both the church and the state, to the secession of Mongolia from the Manchu empire and the establishment of Mongolia?s autonomy earlier and the people?s Government now.“. This was but a statement of the truth from which it was difficult to avoid. The histories of the MPRP and the MPR, written much later, however, could not recognize the impact of Bogdo in a way that the above author did. It only shows how strong was then the influence of ideology on historical research. Scholar Ts. Puntsagnorov wrote: “Historical analysis shows that Bogdo the Enlightened had been assessed as the sworn enemy and an oppressor of the Mongolian people till the last gasps of his breathing”.

Dr. Sh.Sandag, a Mongolian scholar, concluded in his book published in 1971: “The importance of the proclamation of Mongolia?s national independence and the establishment of the Mongolian feudal state under Bogdo khaan, were not thoroughly considered and analyzed. The activities of the statesmen of that time were assessed in a very general way. The years 1911-1919 were termed as the „period of Mongolia?s autonomy?. Because of such approaches I would rather say that the relevant issues were simplified or were avoided and the objective reality was not clarified”. It ought be noted that in spite of such conclusion, there are not many research works and books on the history of Mongolia?s state and party, written since then and containing a thorough and objective assessment of the issue under consideration.

Post socialist research works on Bogdo Khaan

The following was written about Bogdo in the historical book “The Mongolia of the Twentieth Century”, published in early 1990s when a new liberal political atmosphere was setting in in Mongolia: “When speaking of the leaders of the struggle for Mongolia?s national independence, one can not but mention the eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba khutuktu. Although he was Outer Mongolia?s religious leader, all Mongols who professed the yellow faith, worshipped him as their teacher and mentor. The so called „new policy course? of the Manchu empire was opposed by him from the very beginning of its implementation in Mongolia in early 19th century. He considered that its implementation would lead to the loss of „Mongols? fundamental customs”. It concluded that it was understandable that this position of Bogdo the Enlightened had been conditioned by his ministers and the Mongols who had been close to him”.

T.Tumurkhuleg, Mongolian scholar, wrote in 1990 in his article :What kind of person the eighth Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was”: “The eighth Jebtsundamba Khutuktu of Khalkha was one of the persons who were cruelly decried in modern history of „Mongolia under the pretext of a struggle against religion. From what was written in books and sutras and what was said by the old people, he was smart, not stupid, courageous, not coward, and willful, not obedient”.

The fifth edition of the “History of Mongolia? published in 2003 noted the following about the Bogdo: “The Bogdo Jebtsundamba, leader of the Mongolian yellow faith, was able to assert himself on the political scene and became the khaan of the Mongolian nation and the state symbol because he had, from the very beginning of the national liberation movement, firmly stood, for overthrowing the Manchu and Chinese rule and restoring and strengthening Mongolia?s political independence and had strived to unite the Mongols under the banner of the yellow faith”. It concluded: “Bogdo the Enlightened, the limited monarch, passed away on 20 May 1924 when preparations were being undertaken to establish Mongolia as a Republic. His demise removed the grounds for the limited monarchy with the state power vested in people?s government and accelerated the process of transforming the form of governance”.

Baabar observed in his book “The Twentieth Century Mongolia: Migration and Settlement?: “This very day Outer Mongolia overthrew the rule of Chinese Qin regime, lasted exactly 220 years and solemnly proclaimed Mongolia Elevated by Many or independent Mongolia. A 41 year old Tibeten who had an unusually long name Agvaanluvsanchoijinyamdanzanvanchigbalsambuu, worshipped by the Mongols as the eighth Incarnation of Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was elevated as the khaan of this new nation”. He concluded that Jebtsundamba was a „spiritual leader of the Mongols? and noted that there was no other person who would compete with him for the throne.

Tusheet khan Dashnyam, who was most closely related from among the four khans of Khalkha to the golden lineage of Chinggis khaan, could have been elevated as the khaan of the Mongolian nation. But he was not and his words that he was the most senior one among the khans of Bogdo Chinggis lineage, compared to the Jebtsundamba of Tibetan origin” were hardly heard by anybody.

If the Mongolian nobles were, indeed, more prominent among those who initiated and led the national movement to a successful conclusion than Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, a khan of the Golden Chinggis lineage could have been supported. But that was not the case. Instead Bogdo Jebtsundama Khutuktu was followed by all and it showed Bogdo?s influence and the measure of success he had in directing events. It is highly probable that the national revolution started according to his intention and spread and intensified with the support of Khalkha?s nobles. Once the process started and intensified, some of the nobles might have taken activities incompatible with the policy pursued by the Bogdo khaan.

Prof.Sh.Natsagdorj wrote: “If out of the eight Khutuktus elevated in Khalkha, the name of Zanabazar the Lofty, the first Khutuktu is linked to the loss of Mongolia?s independence, then the name of his last successor, the eighth Bogdo is associated with the struggle for the restoration of Khalkha?s independence. But it was not Jebtsundamba Khutuktu or the four khans of Khalkha who effected Khalkha?s secession from the Manchu and China. It was few influential lamas and nobles of Mongolia and several Inner Mongolian officials of that time. They included van Khanddorj of Tusheet Khan league, Bogdo?s confidant da lama Tserenchimed and Inner Mongolian official Khaisan”. His view was supported and „fully justified? by Dr. L.Jamsran, who wrote, elaborating his ideas: “Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu played an important role in the national liberation movement of the Mongols to free themselves from the Qin regime and restore their independence. His elevation to a position of its ideologue and political leader was not due to his efforts only. It ought to be explained in the context of efforts of statesmen like Khanddorj, Tserenchimed, Chagdarjav and others who relied on Bogdo?s reputation in the struggle for the restoration of Mongolia?s state independence and had him enthroned to this end “.

What the above scholars wrote about the Bogdo seems to assert that Bogdo Jebtsundamba did not initiate and lead the struggle for Mongolia?s national independence. Such views, in my humble opinion, are a result of subjective approach towards the historical event.

The consideration of the situation of Mongolian nobles under the Manchu rule, particularly the comparison of their reputation, independence and influence with those of the eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba show that Bogdo had more possibilities and opportunities to initiate and lead the national movement. Bogdo became the foremost leader of the struggle for the Mongolian national independence because he could seize, with a vision and foresight, those possibilities and opportunities.

Bogdo’s treatment in foreign historical works

Count Alfred Kaizerling (1861-1939), who worked for the Governor General of Khabarovsk as an official on special assignment, wrote in his memoir about his visit to Khuree and his meeting with Bogdo: “Khuree is where the gher-palace of Khutuktu, the living Buddha in the East is located. It is to Mongolia what Lhasa is to Tibet. Khutuktu is venerated as much as Dalai Lama. When he reached an adulthood, he was to go to Peking to pay a tribute to the Chinese Emperor and get a blessing at a Buddhist temple there. Since the Peking Government was concerned about the influence of an adult and independent Khutuktu, blessed Khutuktus often happened to suddenly die on their way back to Khuree and their reincarnations were sought and found to take their places. But this Khutuktu did not go to Peking, when he reached adulthood, despite the pressures from Peking and those who surrounded him, postponing his trip under various pretexts. He was safer in Khuree and it was possible in Khuree to prevent from Peking?s direct assassination attempt on his life. His attitude towards Russia was favorable. He hoped that Russia would help him if his relations with Peking turn sour”. He mentioned that he was sent to Khuree by baron Korf to strengthen the friendship between Russia and Mongolia.

He noted the following about his meeting with the Khuuktu: “….. Lamas were lined up along the sides of the stair we were ascending. On the upper floor a young fellow of about 18 years, dressed in a fine Tbetan style was waiting for us. He confidently greeted and invited us to take seats. I presented to him Baron Korf?s personal letter of greeting decorated with state emblem and Emperor?s name in an ornamental script. The Khutuktu sat in his throne with a sacred cushion and invited me to sit on a sofa opposite him. We were offered a Chinese tea served on a golden tray. We had an easy, uninhibited conversation. I then presented the gifts brought for the Khutuktu. He liked a telephone set the functioning of which was interesting to him. But he liked more a music box and was heartily amused by it. He laughed loudly when he heard a brief melody and said that it was like a horse galloping. He immediately had its lyrics translated by his disciple and was quite satisfied when informed of its content”.

The next day count Alfred Keizerling attended a reception given by the Khutuktu. They discussed business and played a chess. He wrote: “When I said, as instructed by Baron Korf, that it was important for Mongolia and Russia to get closer through trading, all those present supported me. Khutuktu inquired if I played a chess. When we were playing chess, devout Buddhists came crawling one after another and got his blessing. On occasions, Khutuktu blessed them with a chess piece he was holding. When doing so he was humming and what surprised me was the tune. It was the one he heard the day before. He checked and then checkmated me while blessing his subjects in the tune of Straus? waltz. I was quite satisfied with my meeting with the Khutuktu and left the palace after offering my gratitude for the reception”. This except from the count?s memoir is, in my opinion, indicative of not only the degree of Khutuktu?s independence, freedom and far-sightedness but also his intention to get closer to Russia. Larson who came from America viewed Bogdo as a “warm hearted person”.

Monseur de Panafie, Charge de?Affaires of France in St. Petersburg reported to his Foreign Minister de Selv on 8 December 1911, based on the information of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs:”Now Mongolia is ruled by Khutuktu who is the most venerable teacher of this nation”. A news appeared in the Frankfurter Tseitung newspaper of 10 January 1912 read: “The crisis in Mongolia has its origin in the failure of the last Chinese (Manchu- O.Batsaikhn) emperors to conceal, driven by their political activities, their dissatisfaction with Khutuktu who is the religious leader of this nation. It was Khutuktu who turned to the Russians. He, just like the Dalai Lama of Tibet, led the people who were discontent with the Chinese sovereign rule”. It also noted: “This second living Buddha, overconfident in himself, entertained unrealistic ideas. Khutuktu is rather old and likes alcoholic drinks and other earthly pleasures that are unacceptable to his religion”.

E.T.Williams of the United States noted about the Bogdo khaan: “Khutuktu is the third highest ranking living Buddha after Dalai Lama and Erdene Panchen Lama” and mentioned: “there were 160 khutuktus in total in Tibet, Mongolia and China and the khuree khutuktu led some 25 thousand lamas and the number of his disciples reached 150 thousand”.

Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu sought the restoration of Mongolia?s political independence and the unification of all the Mongols. An appeal was issued by him to all the inner and outer Mongols to unite and re-establish their nation state. Out of 49 banners of Inner Mongolia, 38 expressed their wish to join the newly independent Mongolia36. F.Moskovitin expressed his views on this issue in his letter of 19 March 1912, addressed to V.Kotvich: “You know, the Inner Mongolian nobles are beginning to aspire for union with the Khalkha. The reason is that they are counting on getting Russia?s support through the Khutuktu. Our Government, however, decided to support the Khalkha only”. Jamsran Tseveen wrote to V.Kotvich on 19 March 1912 that Bogdo, the Radiant as the Sun still had a hope of uniting all the Mongols.

Ya. Korostovets noted when writing about the situation of the Bogdo?s Government in the post - revolutionary Mongolia: “Khutuktu is standing firmly for the friendship with Russia. He is supported by people like Van Khand, Namsrai, Tusheet khan and Dalai van who joined our side”. In other words, his writing points to the critical role that the Bogdo khaan played in the conclusion of the 1912 Treaty between Russia and Mongolia and Bogdo?s loyalty to the friendship with Russia.

It was the eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu who wrote early on the scenario of the Mongolian National Revolution of 1911, based on his estimates of Mongolia?s situation under the Manchu rule and her administrative and legal circumstances and had it successfully played out. It was noted more than once in historical sources that nobody took an independence step without Bogdo?s consent and by 1911 even nobles? meetings in Khuree and their adjournment did not take place without Bogdo?s blessing”. On the other hand, it should be underlined that Buddhism used, at a time, to suppress Mongols? pride, had a direct impact not only on preventing the Chinese culture from penetrating into Mongolia in early 20th century, but also on the unification of the Mongols in the interest of their national independence and on the development of Bogdo the Enlightened, the head of the Mongolian lamaist church into a national leader.

IN CONCLUSION

The secession in 1911 of the Mongols from the Manchu Qin empire and the proclamation of the restoration of their independence opened a new era in their history. Thus a new history began in early 20th century for the revival of the Mongolian nation in Asia with the elevation of Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu to the throne as the khaan of the Mongolian nation and the proclamation of the nation as „Mongolia? and the era as elevated by many? and Ikh Khuree as „Niislel Khuree?.

Obviously, the consideration of the situation of Mongolian nobles under the Manchu rule, particularly the comparison of their reputation, independence and influence with those of eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba show that Bogdo had more possibilities and opportunities to initiate and lead the national movement. Bodo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu became the foremost leader of the struggle for the Mongolian national independence because he could seize, with a vision and foresight, those possibilities and opportunities.

Liuba, Russian Consul General in Khuree noted in his telegram sent to St. Petersburg in January 1912: “Khutuktu is, without doubt, the person who led the event that led to the independence that Mongolia enjoys now41. It is nothing but an expression of the truth.

If Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu could become an object of veneration of Mongolian national religion before 1911, he surely became, after the National Revolution of 1911, not only spiritual but also political leader, a ruler of the Mongols, in the true sense of the word. He is the father of the national revolution which brought about the revival of the Mongols as a nation.

I view the National Revolution of 1911 as a special historical event that occurred in the past 300 years in the lives of the Mongols. It should, if its historical significance is to be considered, take a particularly important place in the lives of the Mongols as a landmark event that restored the foundation for the revival and further existence of the Mongolian nation and laid down the basis for the prosperity of their national tradition, customs and culture.

© This article or any of its parts

may be copied only with the author's permission.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()